Sea-ing Eye to Eye: Kosterhavet National Park

Creating Sweden’s first marine national park was not exactly, how shall I say it, smooth sailing.

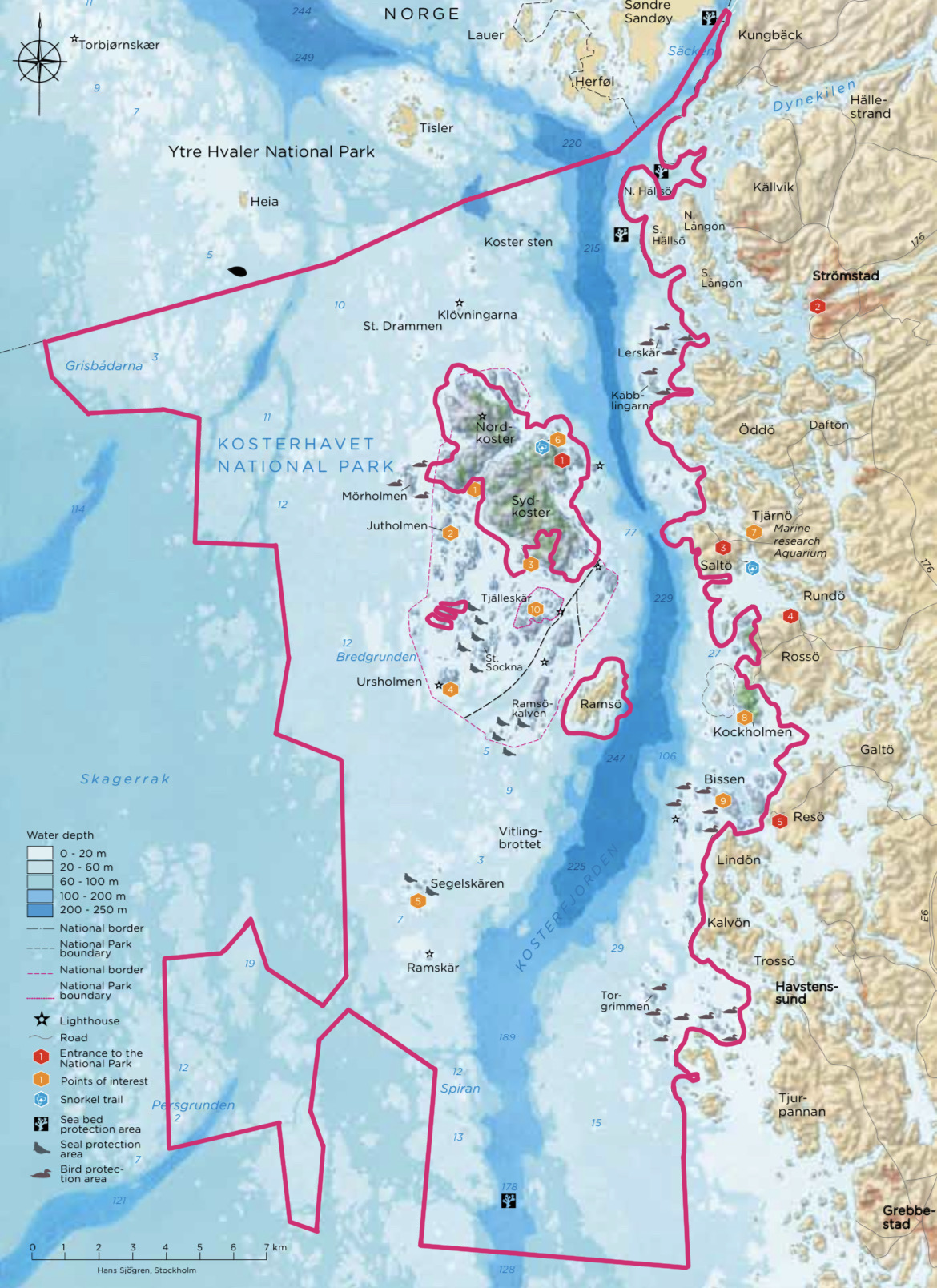

Map of Kosterhavet National Park — Nordkoster and Sydkoster are not included within the national park’s boundaries, but rather protected as nature reserves

Established in 2009, Kosterhavet National Park sits off of Sweden’s west coast. It protects a unique marine habitat and archipelago, including Sweden’s only living coral reef, a deep fjord, and over 6000 marine species.

Only 2% of the park is land, with the vast majority of the formally protected area being water. Two islands, Nordkoster and Sydkoster, sit within these protected waters and are home to about 320 permanent residents. The islands, while not part of the national park, are protected as nature reserves.

We visited the national park and spent a few days camping in the nature reserve, snorkeling around the island (they have snorkeling trails – how cool is that?), and bumping shoulders with goats, sheep, and seagulls. During this time, we also learned about the trials and tribulations that occurred during the park’s creation.

Residents of the Koster islands first learned of plans to create a national park in this area in the 1980s – and were not happy with this news. The local population exploded with criticism, and for good reason – a few years prior, external authorities had turned 2/3 of the islands into nature reserves… without reimbursing land owners. While locals did care deeply about the safeguarding of the islands, an overarching sentiment ran through the community that politicians in Stockholm were making decisions about their resources without any input from those who were affected on the ground. Likewise, fishing was an important local industry and cornerstone of the island’s cultural heritage – and many thought the designation of a national park would eradicate this livelihood.

One of many jellyfish we encountered

Given the level of protest within the community, plans to create the national park were abandoned. However, tourism to the islands skyrocketed, bringing with it a plethora of issues. The combined 12-km2 islands hosted an estimated 2,000 day visitors and 7,000 overnight guests during peak season, and without centralized infrastructure and management, the islands entire archipelago was being overrun by litter and overstaying tourist boats. This coincided with the decline of other local services – the islands’ post office closed, school numbers dwindled, and local businesses struggled. The community began warming up to the idea of the national park, realizing that it could – with local input – provide a means to sustainable community development.

The larger county administrative board (which governed an area much larger than the islands) and the Koster islanders began drafting a national park concept – one that would protect the sensitive marine ecosystem while allowing for the continued economic development of the island. Principally, this meant that fishing, a culturally and economically significant industry, would still be allowed within the national park.

In 2000, after years of discussions between fishermen, researchers, fisheries organizations, and authorities at different levels, the Koster-Väderö Fjords Agreement was reached. This agreement allowed for the long-term protection of the area’s marine ecosystems, habitats, and species, while ensuring sustainable use of the area’s biological resources. Notably, the agreement permits bottom trawling, a not-so-environmentally-friendly fishing technique, in much of the park. A few key provisions of the agreement are as follows:

Specialized “Koster-trawls” are used in order to reduce bycatch.

Trawling is only permitted in areas deeper than 60 meters.

Trawling is prohibited in areas with rare and endangered species.

All parties would collaborate to further develop and co-manage environmentally sensitive and selective fishing.

This agreement was a watershed moment in the development of the national park.

In the general election of 2006, the community voted in favor of national park creation – believing that if done well, the park could turn many of the problems facing the islands into opportunities. New jobs in waste management, tourism, and craftsmanship would be created, with more centralized support and funding. Likewise, the ecological protection of the marine area would be prioritized and maintained by professionals. A visitor center would also be constructed to serve as an educational focal point for the island’s history and unique marine resources.

A pair of curious goats during a hike around Nordkoster

In September of 2009, the park broke ground (broke water?). Today, the park hosts an estimated 300,000 visitors per year and protects nearly 390 km2 of unique marine area. Community members believe that the park has brought significant economic benefit to the island, primarily through tourism. And while the national park’s creation is a success in its own right, questions remain about the balance it strikes between environmental protection and economic sovereignty.

Some environmentalists say prevailing commercial fishing practices – especially destructive methods such as bottom trawling – should be banned outright. Not just in national parks, but period. Should their recommendations be followed, and should regulations be tighter in Kosterhavet to preserve these one-of-a-kind places?

On the other hand, how is it fair for an outside entity or central government – even one with positive environmental intentions – to tell a community how it can and cannot manage its local resources? When a way of life and livelihood is involved – such as the deep traditions tied to fishing on these islands – how does one balance preservation of both cultural heritage and the environment?

I do not have the answers to these questions. I do believe with conviction, however, that conservation MUST be done hand-in-hand with local communities – not to them. The initial community outcry about the national park creation shows that top-down action from a bureaucrat in a city far, far away often fails. As Kosterhavet shows, when communities are engaged in conservation, they can drive meaningful culture shifts, ensuring the long-term protection and local stewardship of globally-significant environments for generations to come.